“The humanities are… a gateway to and instigator of a lifelong activity of free self-cultivation. The changes they provoke in us are not always for the happier, or the more remunerative, or the more civically engaged, but when things go passably well, these changes are for the deeper, the more reflective, and the more thoughtful.”

Those words are from “The Coup that Failed,” by Talbot Brewer (Virginia), published in The Hedgehog Review in 2014.

When I’ve spoken with colleagues about the worry that many students will cheat on assignments by using ChatGPT or other large language models (LLMs), we invariably bounce between three approaches to the problem: “defense”, “offense”, and what I’ll call “no-fence”

“Defense” involves devising assignments and assessments we hope might be, to varying degrees, LLM-resistant. “Offense” involves incorporating the use of LLMs into assignments in specific and guided ways in order to learn how to use it well. Meanwhile, the “no -fence” approach puts up neither measures to guard against illicit student use of LLMs nor markers to guide students in their effective use. It says, rather, if students want to to use LLMs to cheat or avoid work, that’s something they’re doing to themselves, and it’s not the job of professors to paternalistically prevent their students from sabotaging their own educations.

I see the appeal of the no-fence approach. But I also fear it being disastrous.

For one thing, it seems too flip a response to potential damage to intellectual culture. It’s not as if each student who uses an LLM affects only their own education. Rather, one’s use of it can affect other students’ sense of fairness, their sense of what’s acceptable, and perhaps their sense of whether cheating with an LLM is “rational,” given their aims. Cheating may be contagious along multiple vectors, and sufficiently widespread, it turns higher education into charade.

I expect some readers to respond,”what intellectual culture?” or “isn’t higher education already a charade?” They might be thinking: most college campuses, from the perspective of most students, are already not intellectual environments, and much higher education isn’t about learning, but about credentializing and signaling.

I don’t know to what extent that cynical description is accurate. But I do know it’s not an accurate description of all students on all campuses. There remains enough interest among students in knowledge and learning to be concerned about threats to the culture that would extinguish it.

When I hear someone say they’re going with something like the no-fence approach, and I raise these kinds of worries, the response is typically something like the following: the thing I’m worried is threatened by “CheatGPT” is the very thing the value of which we can discuss with our students, so as to get them to see why they ought not to cheat. That is, we should talk with our students about the value of education in the humanities.

What do we say here? If we say something like, “you’ll learn how to write well, and communication is important in the workplace,” we are inviting them to reply with something like, “but in the workplace, we’ll use better and better LLMs or AIs for that, so I don’t need to learn how to write well.” Besides, for most of us, the instrumental value a humanities education may have in making us better workers does not capture what many of us think is important about what we teach, and so such “practical” responses miss something.

Rather, we need to talk with them about how their education is good for them—not (just) good for them in their roles as employees, or consumers, or citizens—but as persons. This means engaging with students in a discussion about what’s important, and what we think they should see as important, for a life well-lived.

And that is why I began with this post with the quote from Brewer’s essay about self-cultivation, about an education that can make a person more reflective and more thoughtful.

This vision of what a humanities education is about informs how we should think of our teaching. He writes:

The ideal teacher of philosophy is not someone whose opinions are to be accepted, but someone whose form of thought is worth emulating.

The Socrates we know is a dramatic persona Plato puts forward as worthy of emulation. I believe that such emulation consists in serious-minded lifelong engagement (engagement “unto death,” as Plato wishes to make clear in the Phaedo and Crito) in the activity of self-articulation, which is to say, the activity of bringing oneself into a more determinate form by bringing oneself into words. Here “articulation” is meant in both of its common senses: We give a more fine-toothed and determinate shape to our views about important matters (i.e., give them greater articulation) by bringing them into the space of words (i.e., by articulating them). This activity requires fidelity to our actual outlook, but it also alters that outlook by finding words for it that we are prepared to live by, hence setting the stage for another, more adequate articulation.

If this is philosophy, then philosophy is continuous with the sort of self-formative activity all human beings go through again and again in the course of their lives, provided they live with even a modicum of deliberateness.

I tell my students on the first day of class, about reasons to study philosophy. Among other things, I say sometimes say something like the following:

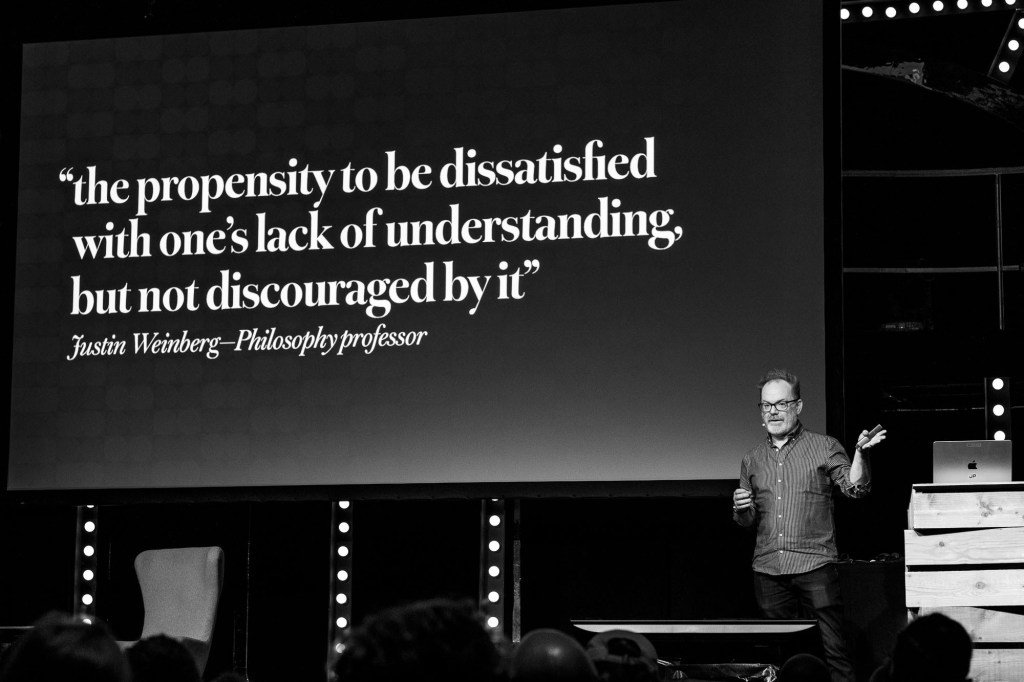

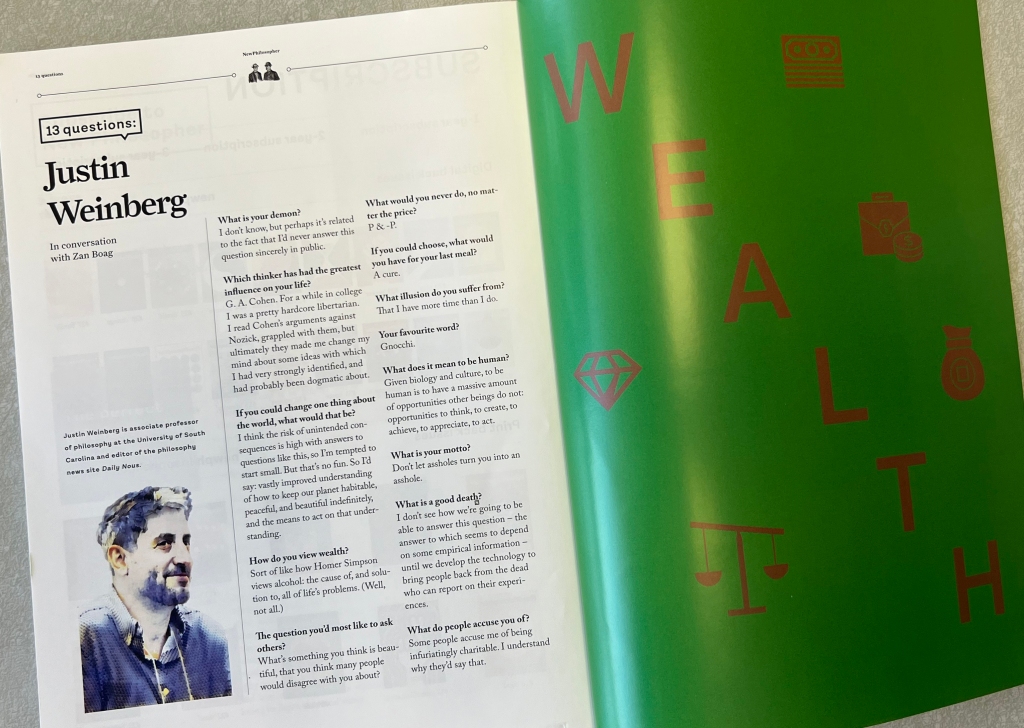

We have a word to describe people who go about their lives doing and believing what they’re told, or what everyone else does, without thinking about why they’re doing or believing these things. That word is “thoughtless”. Most of us don’t think it would be good for us to be thoughtless. Rather, we want to think of ourselves as thoughtful. And we don’t merely want to think of ourselves that way; we want to be that way. We want it to be true that we’re thoughtful. Studying philosophy is one way of becoming more thoughtful.

I imagine most philosophy professors have something like this in their repertoire, and professors in other disciplines have their versions, too. Having something like that as a teaching mission statement is a necessary condition for a responsible version of the no-fence approach.

But is it enough? I say those words to a lecture hall full of students. How many of them were listening? Of those that listened, how many followed what I said? Of those that followed what I said, how many were at all moved by it? And of those who were moved by it, how many will remember it an hour from now?

Certainly it is not enough to say something like this every once in a while, nor to say it on a regular basis. It has to consistently inform and animate one’s teaching, it has to be a lesson that comes through again and again. How does one do that? And how does one do that in the large introductory lecture courses that dominate student schedules at the beginning of their college educations, and are thus so influential in setting students’ attitudes towards their education? (These are not rhetorical questions. Please share whatever answers you have.)

As teachers, we want to believe that what we’re doing is valuable. And we don’t merely want to believe it; we want it to be true. The threat that LLMs and other forms of AI pose to a culture of humanistic learning forces us to think about and articulate what, if anything, makes it true, or could make it true.

We will never convince all students that what we’re teaching is valuable for them in the ways we think it is, and in my view, we shouldn’t hope to, as there are many different goods that can be combined into many different kinds of good lives. So universal assent is not the standard we should hold ourselves to. Rather, we just need to reach enough students—enough to protect from threatening technology what we believe is valuable, and enough for us to honestly believe that what we’re doing with our teaching is actually good.

If we can figure out a way to do that, then I think I’d find myself more squarely in the no-fence camp. Can we?

[originally posted at Daily Nous]

Leave a comment